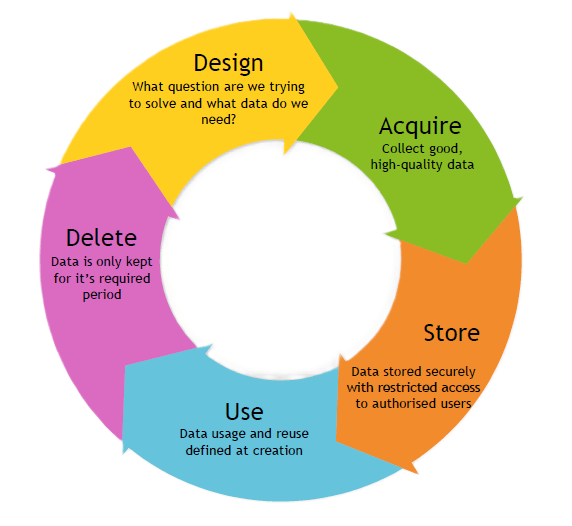

The goal with the DASUD Framework, is to help you launch your own flavour of Data Governance within the shortest period of time – which, at current publication is under 6 months. By contextualising your needs to the DASUD framework, I am confident that it will be your launching pad into something greater that not only becomes your flavour of a Data Governance Model but something that lasts long after you have moved onto your next challenge! To read more about the origins of the framework, click here. To understand how it was used to implement a Data Governance Framework in a medical research setting, then read on!

The Medical Research Context

Medical research is a critical field that contributes to advancing healthcare, understanding diseases, and improving patient outcomes. For those outside looking in, the landscape can be complex, particularly when navigating legal and ethical frameworks. Below is a breakdown of the main types of medical research, their characteristics, and whether specific laws or regulations typically apply to them.

1. Basic Research

Definition: Basic research focuses on understanding fundamental biological processes. It often involves laboratory studies using cells, molecules, or animal models to uncover the mechanisms behind health and disease.

Example: Studying how specific genes regulate immune responses.

Legal Applicability:

- Laws: Generally governed by institutional policies, ethical guidelines, and animal welfare laws (e.g., Australia’s Animal Research Act or the US Animal Welfare Act).

- Considerations: No direct patient interaction, but stringent oversight for experiments involving animals or genetic modifications.

2. Clinical Research

Definition: Clinical research involves human participants and aims to assess the safety and efficacy of medical interventions, such as drugs, devices, or procedures.

Example: A Phase II clinical trial testing a new cancer drug.

Legal Applicability:

- Laws: Highly regulated, often requiring adherence to frameworks like the Declaration of Helsinki, Good Clinical Practice (GCP) guidelines, and national laws (e.g., Australia’s Therapeutic Goods Act).

- Ethics: Ethical approvals from Human Research Ethics Committees (HRECs) are mandatory. Researchers must also ensure participant informed consent.

3. Epidemiological Research

Definition: Epidemiological studies examine patterns, causes, and effects of health conditions in populations. This research can identify risk factors and inform public health interventions.

Example: Investigating the link between smoking and lung cancer in a large cohort study.

Legal Applicability:

- Laws: Compliance with privacy laws like Australia’s Privacy Act 1988 or GDPR in the EU is critical when handling personal health data.

- Ethics: Anonymisation and secure data handling are essential to protect participant privacy.

4. Translational Research

Definition: Translational research bridges the gap between laboratory findings and clinical applications, often described as “bench to bedside.”

Example: Using findings from basic research to develop a new vaccine.

Legal Applicability:

- Laws: Depending on the stage, it may fall under both basic and clinical research regulations.

- Ethics: Collaboration between researchers, clinicians, and regulatory bodies ensures compliance with applicable laws.

5. Health Services Research

Definition: This research evaluates healthcare systems, policies, and practices to improve efficiency and patient outcomes.

Example: Analysing the impact of telemedicine on rural healthcare delivery.

Legal Applicability:

- Laws: Privacy laws are crucial when using patient records.

- Ethics: Minimal risk studies may still require ethical approval and adherence to governance frameworks.

6. Public Health Research

Definition: Public health research focuses on preventing disease and promoting health at a community or population level.

Example: Studying the effectiveness of mass vaccination campaigns.

Legal Applicability:

- Laws: Often intersects with public health laws and mandates (e.g., Australia’s Biosecurity Act).

- Ethics: Balances individual rights with community benefits, requiring thorough ethical reviews.

7. Qualitative Medical Research

Definition: This research explores patient or healthcare provider perspectives through interviews, focus groups, and other qualitative methods.

Example: Assessing patient satisfaction with post-operative care.

Legal Applicability:

- Laws: Privacy and confidentiality laws govern data collection and storage.

- Ethics: Informed consent and ethical approval are necessary, even for non-invasive research.

8. Genetic Research

Definition: Genetic research investigates the role of genes in health and disease. This can involve genome sequencing, genetic testing, or editing.

Example: Studying genetic predisposition to heart disease.

Legal Applicability:

- Laws: Heavily regulated due to ethical concerns, with laws like Australia’s Gene Technology Act 2000 or the US Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act (GINA).

- Ethics: Strict oversight to prevent misuse of genetic information and ensure participant consent.

Why Understanding Research Types Matters

For non-medical researchers, recognising the distinctions between research types helps:

- Ensuring Compliance: Each type is subject to different legal and ethical standards. Understanding these nuances avoids potential violations.

- Facilitating Collaboration: Knowledge of medical research frameworks fosters smoother interdisciplinary partnerships.

- Improving Research Impact: Tailoring methodologies to align with ethical and legal considerations enhances credibility and public trust.

Medical research spans diverse domains, each with unique purposes, methods, and regulatory considerations. For professionals entering this field, understanding these categories and their associated legal frameworks is crucial. While laws vary globally, adherence to ethical principles and governance frameworks is a universal requirement. By aligning research practices with these standards, non-medical researchers can contribute meaningfully to advancing healthcare.

For more information on what you need to do to start this process, check out my Definitive guide to Implementing Data Governance. The remainder of the article requires that you view it side-by-side with the following PDF which demonstrates how it was implemented at a medical research institute (MCRI), please download and use the material here: https://figshare.com/s/418318db68f541feb955.

I have made it free to use, for non-commercial purposes with the right attribution. The IP remains with the Murdoch Children’s Research Institute and if you’d like to use it for commercial purposes, please get in touch with their IP department. They’re a lovely bunch of folks that will gladly help you navigate your request.

Principles First

When approaching this framework as a Data Governance professional, you can apply specific principles for each of the 5 questions. When I implemented DASUD at MCRI, [Page 6] I:

- Took into account all the Australian State Health Laws,

- moved to the national health laws and

- then finally the countries with whom MCRI partners with. This meant the laws in other countries and taking the one with the stringiest rules, which at present is GDPR.

- As a research based organisation, I also checked the research legislations including those that impact Universities.

- Furthermore, the Code is another one that needed to be addressed.

With all of those considerations the principles of DASUD for MCRI was formed.

Design

Within Design [Page 8] we have the key principles focused on research data

- we ensure that the data capture is limited (don’t get more than you need – JUST IN CASE is a bad idea and point them to the data breaches for anyone that says otherwise…),

- classified as per the organisations rules (and remember these will change when the data is shared),

- metadata is tagged (so we know where to search for it),

- have accountable people (no federated model can have “all the answers” – however if your organisation is setting up central archiving function, reach out to me and I will help) and

- have a “how-to” for each of them (cause we all know, fluff is fluff until the rubber hits the road).

Acquire

Within Acquire [Page 9], we:

- check our existing library (did you know that there is a huge cost in capturing similar data again in the research world – it was mind blowing!) to reuse any asset,

- collect high quality data (for MCRI, this was defined as Complete, Accurate and Consistent),

- utilise existing ontologies (this helps with ensuring the data collected can be matched with international medical standards to help with reuse), and

- that at least internally, all data should be made available to internal MCRI people (practically this was via utlising the metadata for discoverability instead of the actual source data).

Store

Within Store [Page 10], the goal was to:

- reinforce classification (if you’ve done it back in Design – you won’t have anything to worry about here),

- have metadata tagging which drove the storage location.

- With the ever increasing cost of storage, we encouraged people to archive their data with a clearly defined “archiving” status. One unexpected behavioural challenge which I was unprepared for – users thought of digital storage as inexhaustible. When it was physical, they had to order a new physical storage cabinet, fill it with external hard drives, or USB sticks (or floppy disks) and then have an actual box to store it all in. Without that physical, tangible, and sometimes painful process, going digital means it’s easy to just store everything…. INDEFINITELY.

HARD. NO! As a Data Governance professional, and a Data Savvy human, don’t keep anything longer than you need to… and NO… don’t think about pushing it down the line for “someone else” to decide. Have the hard conversations before the project finishes – cause we all know that the “post-implementation support budget” is minimal, if there at all… [that’s a whole other rant that I don’t want to go down… yet]. Furthermore, when (and not “if”) this gets discovered, the legal and regulatory ramifications from holding data beyond it’s required period is just unnecessary risk.

- And finally, we needed to preserve the lineage of the data asset to enable research integrity checks could be verified.

Use

Within Use [Page 11], it was all about:

- ensuring the data was used in line with the purpose for which it was collected,

- making sure it can reused as much as possible,

- having an associated sharing agreement and

- ensuring that any process that is being used to utilise the data is reproducible.

Delete

And finally within Delete [Page 12], we wanted to:

- ensure that we do not keep data beyond it’s useful date. As such, we ensured that retention periods were defined, with periodic checks on the assets held internally and

- confirm that when when it is finally deleted, we would ensure we know who took part in what study and what data we had (in a generic manner) and the period that we held their data.

Closing Thoughts

Implementing a data governance framework is just the beginning of your ongoing journey. What it will demonstrate to the organisation – is how everything is interrelated and that you can’t do one without the other. Without classification, you can’t store data properly. If you store it, how do you find it? And why are you doing all of this? Either to make more revenue or to improve the lives of people in a not-for-profit environment. Everything is connected, and at times, it can feel overwhelming. But you’re not alone. Check out my Definitive Guide to help guide you on this process. If you’d like assistance or advice with your Data Governance implementation, please feel free to drop me an email here and I will endeavour to get back to you as soon as possible. Alternatively, you can reach out to me on LinkedIn and I will get back to you within the same day!